In the early hours of Wednesday morning, two small boats carrying 23 refugees from the besieged Syrian town of Kobane set off from Turkey's Bodrum peninsula, bound for the Greek island of Kos. Presumably, their aim was to enter the EU in search of asylum and a new life.

The boats, however, sank. At least 12 of the passengers drowned, including five children. One of these was a three-year old boy named Aylan Kurdi, whose body was recovered by the Turkish coast guard laying face-down in the sand. A Turkish news agency recorded these images and within hours they were on the cover of newspapers worldwide.

Such graphic images generated consternation and controversy to an extent I don't think we've seen before in the Syrian crisis. Many decried the image--a small boy, his face clearly recognizable--as simply too heart-wrenching to distribute with any decency.

My own view is that, as traumatic as the image was, it helped galvanize the international community--outside Europe, at least--in a way no manner of mass rape campaigns, summary executions, sealed lorries, barrel bombs, or antiquities destruction so far has. Given subsequent policy changes in Britain, the 15-fold increase in donations to MOAS (the Migrant Offshore Aid Station charity), even the commitments made on the Canadian campaign trail, I'd say the evidence suggests the photo was worth it.

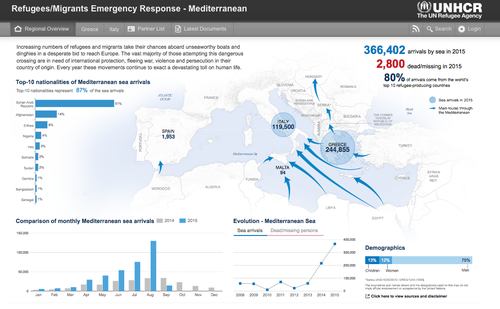

But the photo isn't really what matters here. As the UNHCR has made abundantly clear, this is not a new phenomenon. People have been risking their lives to escape Syria's horrifyingly complete implosion for years now.

As Ian Bremmer points out, you would too.

Nor should we be thinking that mass migration--forced or otherwise--is something strictly limited to the charred remains of a once-reasonably stable state. The Guardian's Datablog has some good data on just how dangerous a place the Mediterranean has become for people searching for a better life.

My point here is not to suggest that the forced migration of millions is an easy problem to solve. Indeed, I'm about as big a supporter of bombing the hell out of ISIS as you can get.

Palmyra's magnificent Temple of Bel stood for nearly 2000 years. On Sunday, the Islamic State blew it up https://t.co/ts9Do2mO9h

— Liz Sly (@LizSly) August 30, 2015

More drone strikes, please. https://t.co/wG8CKnVjD6

— Sean Clark (@DrClarkIPresume) September 1, 2015

But even I recognize that an aerial campaign--as good as it makes its supporters feel--has exactly zero prospects for successfully reuniting one of the most unstable and deeply divided places on the planet. No Kurdish army is marching on Damascus. No coalition of secular liberals are going to throw back Assad. No Western ground troops are going to adhere to the Pottery Barn rule and return stability to the region.

There are no good solutions, only fairy tales. All we can expect is more killing.

Main cause of civilian deaths (and dislocation) in Syria is not ISIS. pic.twitter.com/1bysIrJihc

— Roland Paris (@rolandparis) September 3, 2015

This leaves Canadians with only one plausible option with which to raise welfare gains in the region: let more people in.

We are not going to fix Syria; so let's let them come and make a new life here. It's a no-brainer foreign policy. And yet, the backlash to such ideas is overwhelming. In Britain, the argument commonly heard is that there is 'no more room.' That idea, as Jeremy Cliff has observed, is idiotic.

People tweeting at me that UK is too full for new migrants. Took this photo yesterday 30 minutes from Manchester. pic.twitter.com/34c9nb8TK7

— Jeremy Cliffe (@JeremyCliffe) September 1, 2015

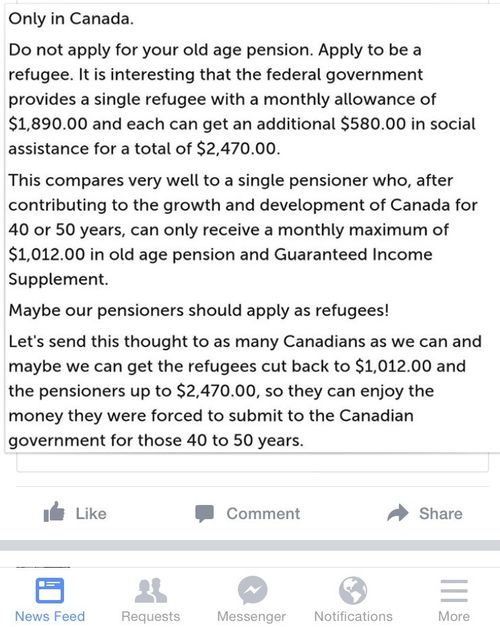

Lest anyone here scoff at the small-mindedmness of some Little Englanders, let's consider some of the rhetoric that is all-too-common inside our own borders. A useful example is a meme that pops up every now on then on social media. It's basic premise is that a) Canadian resources--like the British land example cited above--are not only finite but under acute strain; and b) what volume of foreigners we do let in now causes an untold burden and leaves current citizens without.

Needless to say, I don't find this argument particularly convincing. The idea that Canada is somehow already too generous in its dealing with the world's massive backlog of refugees beggars belief. Such a view is shamefully incorrect, and easily exposed for its ignorance and selfishness.

Let's be clear. Out of a population of over 35 million, Canada currently accepts just 10,000 or so refugees per year--a number just 1/60th of 1% of the total global refugee population of 60 million.

Scott Gilmore has already made the comparison with a contemporary peer. "If one compares the economic ability of a country to accept refugees," he writes, "Canada is accepting one-quarter of a refugee per $1 GDP per capita. Germany is accepting 80 times that amount, or 17.4 per $1."

A comparison of the current refugee proposals from @pmharper, @ThomasMulcair, @JustinTrudeau. Is no one embarrassed? pic.twitter.com/7nrvwQJ5g5

— Scott Gilmore (@Scott_Gilmore) September 4, 2015

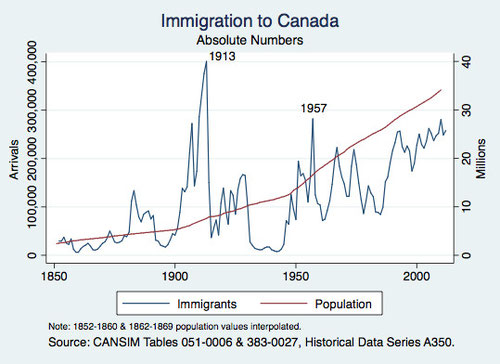

The German example is worthy of emulation, in my view. But an even better comparison is to put these numbers in historical perspective: how generous are we, compared to times past, in our willingness to let outsiders come and start a new life?

If we dig through the StatsCan data and look at immigration more broadly--the time series available back to Canada's earliest days--we get a sense of how, in absolute terms, arrivals volumes have not kept pace with national population growth over time, particularly in the last half century. Population has gone up and up, but arrivals figures over the last several decades have not come close to reaching our previous peak more than a century ago. Nor have they even, despite a doubling of our population, reached the postwar peak reached in 1957.

Canada took in 400,870 immigrants in 1913, with a pop of just 7.6 million (StatsCan A350 & 383-0027). Today we are 34 million.

— Sean Clark (@DrClarkIPresume) September 4, 2015

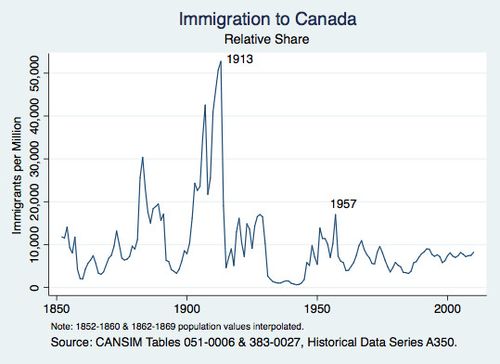

The picture becomes even clearer when we calculate relative shares. How many foreigners have we let in per million citizens, and how has this evolved over time?

The answer is yet another embarrassment to those who claim the national fabric can not handle current migration flows. Canada has never been so rich, and yet hardly ever more closed off to the world's poor. So much so that flows could double and they still wouldn't be at the 1957 level--to say nothing of the heady, pre-Great War period.

The lesson is that for all our wealth and prosperity, we have turned our backs on so many of the world's poor and denied them the prospect of a better life. There was a time when our rising prosperity was coupled with a call for the world's less fortunate to come and try their hand in a grand national experiment called Canada. There is not a shred of historical evidence that suggests we shouldn't return to that mantra.

Sean Clark

Sean Clark

Write a comment