This spring I wrote a paper for the the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada's (DFAIT), under their International Security Research and Outreach Programme (ISROP). It basically was a chance for me to extend my earlier thinking about China's economy and environment, and take a look at China's domestic security and international position.

What follows are the executive summary, a couple of quick thoughts, and a link to the full text.

For anyone interested in the program--and it is a great one--the current ISROP research themes can be found at:

http://www.international.gc.ca/isrop-prisi/index.aspx?lang=eng

Executive Summary

For all the fear and concern accompanying discussions of China’s spectacular reemergence, the central conclusion of this paper is that current behaviours and contemporary trends point to a future where China maintains its current satisfaction with the international system. In terms of security, China’s neighbours are too weak individually to pose much of a threat, yet at the same time powerful enough in tandem to make military expansionism impractical. This is not to suggest that China lacks those who yearn for the return of lost territory, such as ‘rebel’ Taiwan or the ‘nine-dash line’ in the South China Sea, but that there is very little reason to think these revanchists have the strength to carry the day. This is in large part due to the central pillar of the CCP’s rule: the achievement of steady economic growth. For all its flaws, the CCP has overseen the most impressive economic catch-up of all time. The conclusion amongst the Chinese public is that continued communist rule is thus a laurel worth bestowing.

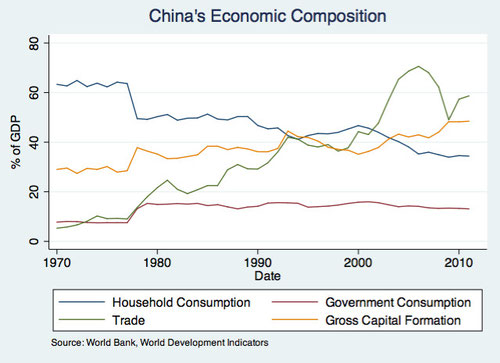

The remaining key aspect of great power satiation is wealth. Here again there is nothing to suggest that China will find the international system discomfiting. Chinese exporters have gone from strength to strength, with little opposition from overseas markets shown. Rather than slapping on anti-dumping duties and erecting tariff walls, foreigners have lined up to buy cheap Chinese goods. Moreover, what little tension does exist can be expected to diminish as China’s economy continues its trend of shifting away from exports and more towards domestic consumption. The consequent forecast is for smaller current account surpluses and thus even less international wrangling over Chinese market gains.

In short, the future of economic growth in China will lie primarily on the strength and vigour of the domestic reforms that must now be undertaken. Even here there is good reason for optimism, given that a clutch of economic reformers has been installed at the very heights of the Chinese economy. If the success of these able technocrats in the late 1990s is any indication, markets will be further freed and the concomitant productivity gains made plentiful. Such a result would set the stage for a China quite unlike the Germany of 1914, a power deeply unsatisfied with the contemporary international system and surrounded by mutual hostility. Instead, China would appear much more similar to the United States of 1890, steadily—and contentedly--gaining in power and influence but to the anger and detriment of few.

Key Graphs

When thinking about the Chinese economy this is the graph I care about most. High levels of capital spending don't bother me--China still has endless numbers of rural villages that need

hospitals, expressways, and new housing. And since I've yet to see any data on the breakdown of these dollars between industrial capacity (which is probably at excess levels, itself often

the product of crony capitalism) and still-needed infrastructure, a high number alone is no cause to freak out. We need a better sense of where this money is headed before that

happens.

What really matters to me is the (currently flat) household consumption line. Growing consumption means Beijing's heavy-handed efforts to rebalance the economy are working; a falling share means more unnecessary factories and capital misallocation--which is as big a political failure as it is economic.

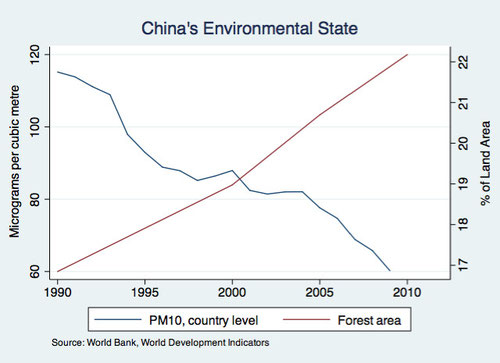

National-level environmental metrics are much harder to find than GDP accounts, but these are two handy indications of just how good it is for the environment when you grow rich.

Timberlands have grown as private property reduces the incentive to cut down trees, and a growing, environmentally-conscious middle class demands ever more park space.

PM10, a useful measure of air pollution, has gone down nationally, too. Itself the product of the same forces--though with the caveat that while the slow elimination of Maoist factories

from the countryside may improve air quality overall, China's continued reliance on coal and growing urban sprawl has concentrated air pollution in the largest cities.

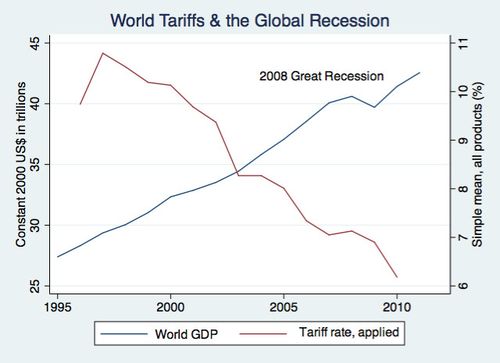

This one speaks to how good we still have it at the international level. Here we have the 2008 Great Recession, the hardest shock to global prosperity since the 1930s, and yet tariff rates

have continued their descent downward.

Imagine if Tokyo confronted that fact in the 1930s and 1940s. Perhaps the decisions it made would have been different.

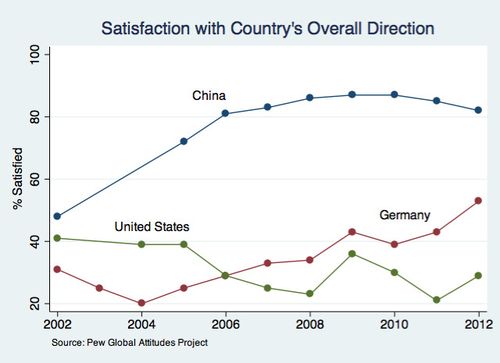

As is, China doesn't seem overly worried about things.

Nor, for all of China's problems, is the public too upset either. A torrid economic rise leads to real growing pains. Yet better that than the alternative.

Sean Clark

Sean Clark

Write a comment